My Effin’ Life by Geddy Lee: A book review

Originally published on Medium on Jan. 16, 2024.

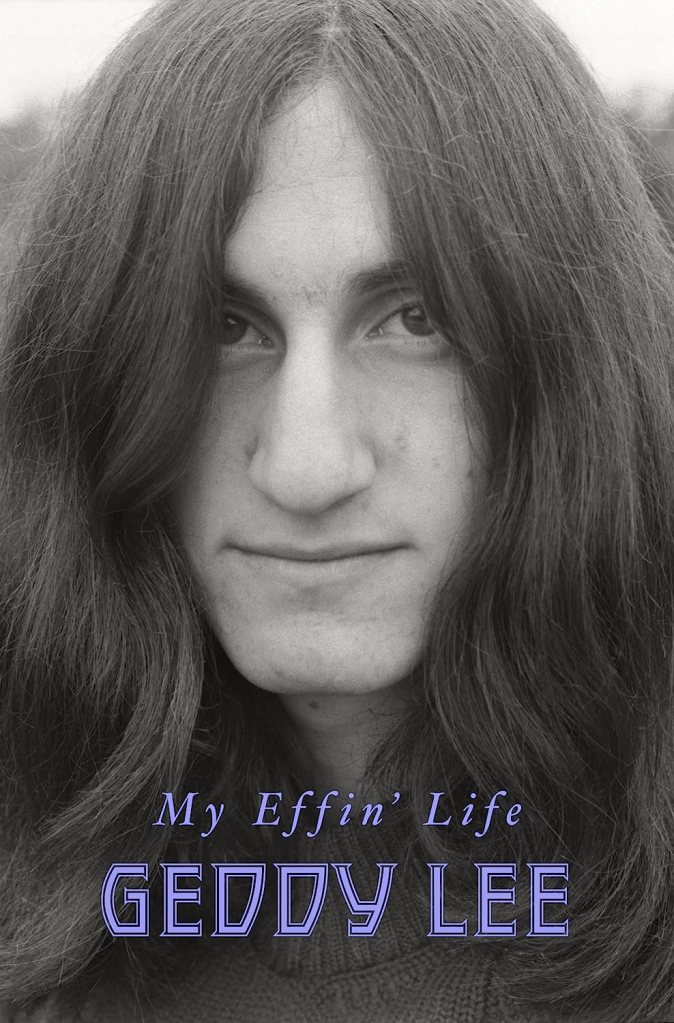

My Effin’ Life is told in a voice that’s uncompromisingly, unmistakably Geddy Lee’s.What other voice would you expect eh?Funny. Sad. Tragic. Inspirational. Surprising. Nostalgic. The 500-plus page words-and-pictures journey is all of that and more.

To be sure, this isn’t a Neil Peart book. The late great drummer and Geddy Lee’s bandmate had a humorous side and he would sometimes try his hand at improvisational writing. But Peart’s books were very structured, very serious, very — dare I say it — literary and erudite as was the man himself.

Not to disparage Lee — he’s no dummy, for sure — but his memoir reads more like an audiobook. You can almost hear his voice throughout the book and you give him wide latitude to have fun as he’s telling his story. Why, readers only have to look at the title to know what they’re effin’ getting into.

My Effin’ Life goes back to Lee’s childhood, including his family’s move to the suburbs of Toronto. It may have been like “heaven” for Lee’s parents but it was something entirely different for kids. Like Rush’s song “Subdivisions” put it, it was a place that had “no charms to soothe the restless dreams of youth.”

And so Lee takes us along as he escaped the ’burbs and all the heartache and horrors of his early life with the help of his music.

Along the way, he recounts in heartfelt and heartbreaking detail the horrors that his family endured during the Holocaust and losing his father when he was only 12. Lee reminds readers several times in the book that he isn’t religious but he does pay homage to the faith of his fathers and mothers, especially how Judaism treats the death of a loved one. It’s a lesson that serves him well throughout his life — including how he dealt with the loss of Peart and others.

Recalling his father’s death, Lee writes of the 30-day mourning period called sheloshim following shiva and adds in a footnote:

“About six months after your loved one is buried, the gravestone is unveiled, and you’re told that your grief should now turn to remembrance. I find that a rather beautiful concept and a fine example of age-old rabbinical wisdom.”

The bulk of this book is about music, in particular the long history of Rush.

Considered one of the greatest bass players in the world, Lee writes of growing up amid the heady rock scene of the late 1960s, catching the bands in Yorkville Village. “It’s true, is it not, that out of chaos sometimes comes order? It can focus the mind,” he reflects. “For in retrospect I can see that bass had always been, you might say, in my blood and bones.”

He also writes of singers who were a great influence such as Robert Plant, Rodger Hodgson, Paul Simon and Joni Mitchell. Lee, who has often been ridiculed for his high-pitched voice (and who is self-effacing enough to point it out himself, as well as his big nose), writes of how he realized that by singing in a higher octave he discovered power in his voice.

He adds after watching the movie Coda recently that “it dawned on me that my earliest vocal style may also have been rooted in my childhood, listening to the stories of what my parents had endured in the camps, suffering all that bullying and alienation, so that when I did begin to sing it did come rushing out as a screaming banshee. I am releasing all those suppressed emotions just by stepping up to the mic and screaming ‘Ooh yeah!’”

Lee writes of how Rush’s music was influenced by artists from many sources. And that’s a good thing, he says.

“The more influences one has that are then filtered through one’s own personality, the more one ends up with a style and a sound that one can legitimately call one’s own. If you have three bands influencing you, you’re derivative; if you have a hundred, you’re original!”

And he takes readers along other journeys that are meaningful to him, from tasting fine wine and the joys of traveling to birdwatching and baseball.

Lee can be candid. This reader and longtime Rush fan was surprised at the influence of drugs during his career. I suppose I knew the band members liked the occasional illicit drug in the early days (just listen to Caress of Steel or “A Passage to Bangkok”) but I didn’t realize how much Lee indulged in drugs, including cocaine and acid, and how long it went on for.

I was also surprised at how Lee still holds on to grudges against certain people who have slighted him over the years. After all, he did sing these lines on “Wish Them Well”:

“The ones who’ve done you wrong

The ones who pretended to be so strong

The grudges you’ve held for so long

It’s not worth singing that same sad song.”

Lee admits he is “a motherfucker who bears a grudge” as when he took note of of some people in the business who have slighted him, and those who wrote gossip about his beloved bandmate Peart (and ended up in his “memory’s special blacklist”). But he does keep singing the same sad grudge song and it may be worth remembering that even a good, clean polite Canadian boy like Geddy Lee has probably pissed off a few people along the way. For instance, there was a tempest in a rock and roll teapot between The Runaways and Rush where the former claimed they were treated badly by the headliners — which Lee disputed.

Still, there’s no disputing the disdain that Lee expressed toward Fleetwood Mac during a 1979 interview. The interviewer tells Lee that Fleetwood Mac spent $1.1 million to record Tusk, the followup to their Rumors LP, and asks if Rush would invest that kind of money into an album.

“I don’t think you could,” he said. “You’d have to be pretty bad to spend that much money.”

To be sure, Lee looks high as a kite in that interview. He was also very young and probably enjoying the heady hubris of his band’s uncompromising approach to music at the time.

Lee is 70 now and age and wisdom have, perhaps, softened some of that brashness.

For instance, while Lee doesn’t indulge in politics in his book — oh, how I wish I could hear his opinions about a guy like Trump! — he does touch on the anti-vaxx movement during the pandemic at one point and waxes philosophical about the term free will.

Lee writes about the blowback he received for posting a photo of himself wearing a mask with “loudmouths” quoting “free will” back at him “as if those two words alone constitute permission to act without regard for the well-being of others, to ignore science and to rid ourselves of responsibility for the consequences of our actions.”

Of the concept of free will, he writes, “I’ve read the book and the fine print. Life is not so black and white; we live in its grey areas.

“I’m afraid that life is too complicated for us to simply ‘choose free will.’ You can’t just say or do anything, prizing your rights over everyone else’s. Generations of scholars (notably the Talmudic ones) have spent their lives arguing in byzantine detail the interpretation of society’s rules, because it all depends on context: when, exactly, will I choose free will? Over the health of my kids or the happiness of my wife? Over the responsibility not to pass a disease on to my fellow citizens? A caring, functional society needs constraints and responsibilities. Terms and conditions apply.”

Pearls of wisdom like that and the rabbinical lessons of dealing with grief, mixed with gems of humour, his loving affection for family and so much humility amid his tales of struggle and rock stardom and tragedy, makes this a must-read. Not just for Rush fans but anyone who’s invested in life.

Who can argue, for instance, with:

“I used to advise my kids or my pals whenever they were at a crossroads to just keep moving forward with positive energy; either you will find the answer or it will find you.”

Of course, this being Geddy Lee, he ends that statement with: “Hmm..Note to self.”

Leave a comment