Dishing out justice and integrity in the Ventura DA’s office

This review originally published on the Medium site The Howling Owl on Jan. 22, 2025.

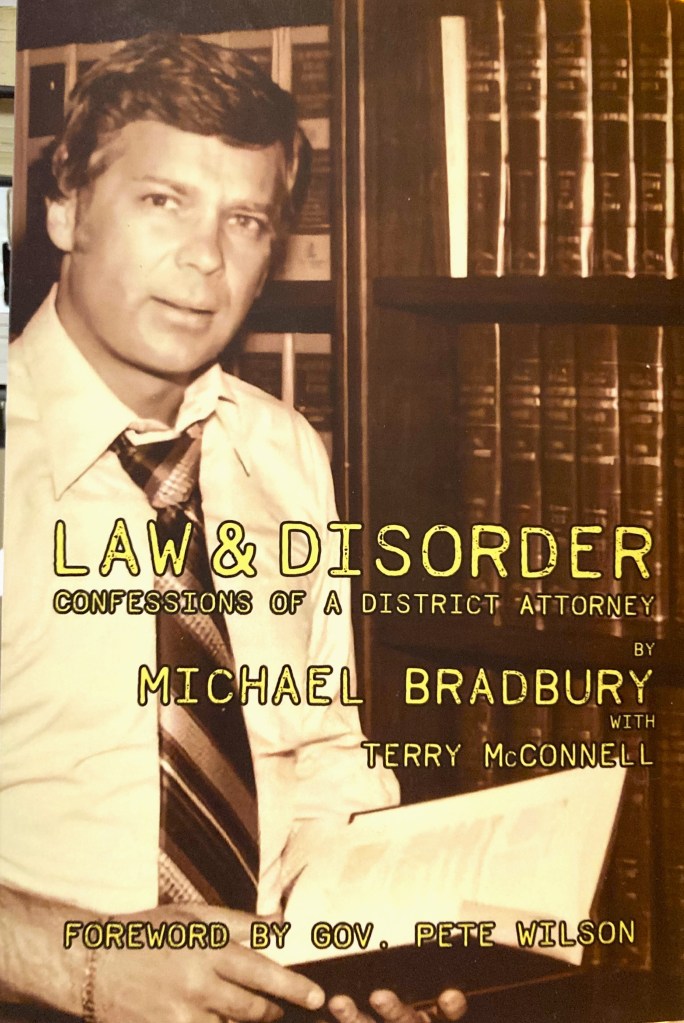

Michael Bradbury has led a helluva life and the book he wrote with Terry McConnell, Law & Disorder: Confessions of a District Attorney, tells a helluva story.

I mean that literally. As in, some of the things and people he dealt with in his professional life were hell.

At least, that’s what it seems like to an outside observer. Bradbury would probably disagree.

There is a lot of ugliness and corruption that the former DA in Ventura County, California grappled with during his storied career. I mean damn ugly and evil stuff, like serial rapists, cold-blooded killers and gruesome autopsies he has witnessed.

Bradbury has dealt with the kinds of people and things that would cause those with weaker constitutions to crumble. During my years working as a reporter and editor at various newspapers, I’ve always marvelled at how emergency responders and people in the legal profession could cope with the devils of our baser natures with distinction and even honour. Bradbury joins in the ranks of these people of honour and heroism.

There’s so much more in Law & Disorder than just his life’s story and grisly crime details (which, to his credit, he warns readers about in advance). These pages are also a primer in some ways of how one can, and should, live a life.

Former California Governor Pete Wilson, in his foreward, seems to recognize that in Law & Disorder:

“It is the accumulated practical, useful and very entertaining wisdom of the Honorable Michael D. Bradbury, learned from his 33 years as a prosecutor and the repeatedly elected District Attorney of Ventura County, California,” he writes. “It is very personal. It teaches more about human nature than the finer points of criminal law.”

And Terry McConnell, who helped tell Bradbury’s story, captures the essence of the man and his life in his preface by saying the book is the story of integrity. (Full disclosure: Terry McConnell is a good friend.)

During the 18th months he worked with Bradbury, McConnell says, “I learned quite a bit, not just about crime and punishment in Ventura County, but about the integrity it takes to be a prosecutor there, as he was for so many years, and about the measure of a man who has that kind of integrity.”

He adds: “This is real life in all its flawed yet glorious detail, and in its telling are the lessons that can make all our lives better lived, and our spirits more whole.”

But let’s get back to the book, shall we? Despite the grisly crimes and characters he’s encountered, there is humour in Law & Disorder and homespun expressions that will endear the author to the reader. Some may say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover but how can you not be sold when you read this quote of Bradbury’s on the back:

“When a jury orders lunch and the order is for 11 hamburgers and one hot dog, you know you’re in trouble.”

Or when the reader stumbles on some hokey but loveable cliches like the time he was “happy as a clam,” or when it was “raining like Noah’s ark” or Bradbury remembers some “cowboy” prosecutor who would “go off the reservation if not watched carefully.”

Although he uses aliases for many people he writes about, Bradbury’s portraits of his partners (and opponents) in crime leave a lasting impression. Like Judge Dick Love who, he says, “lived up to his name. You had to love him because he was mystifyingly eccentric.”

Bradbury writes of one of his early encounters with Love as a prosecutor:

“The judge came to the chambers’ door and looked out into the courtroom. He was taller than I remembered, and he looked like Darth Vader in his black robes. His face was so dark it could have passed as Vader’s breathing mask. He glared at me. I quickly looked down at my files.”

Bradbury also writes he has always been “intrigued” by pathologists, most of whom were very professional, “but theirs was a career that did seem to attract a sort that didn’t always appear normal. Of course, sometimes I wondered if my opinion of what was normal was normal.”

The author is not beyond admitting when he made mistakes — and was sometimes called out on them. There was a country music singer Joanie Mosby who he ran into at the Ban-Dar honkytonk nightclub and saw performing a song about “how unhappy she was with the injustice she had suffered at my hand — and I wasn’t even the DA at that time. I was forever enshrined in a bad, sad country music song.”

In another passage, Bradbury ponders whether he should file charges against a waitress, Rebecca Long, who he had prosecuted earlier and who exacted a measure of revenge against him (which I won’t give away).

“I suddenly I wished I had looked into the cause of Rebecca’s situation more carefully before making the decision to prosecute. There are always extenuating circumstances. It’s a matter of balancing the seriousness of the crime with the facts that got them into the mess in the first place,” he realizes.

Being a DA means sometimes paying a steep personal price for your decisions. Bradbury tells one story about a former dear friend who never spoke to him again after one case.

“I learned the hard way there can be a price for doing your duty, one that sometimes makes you question what the right thing to do precisely is,” he writes. But then Bradbury recalls former DA and mentor Woodruff ‘Woody’ Deem who reminded him that the “alternative is unacceptable. After all, the prosecutor is the principal doorkeeper to justice for all.”

A couple of chapters seem to veer off into blind alleys and past personal moments but he brings it all together. Chapter seven, for instance, recounts his experience with an apparent ‘Mafia kingpin’, a country music star (who I won’t reveal), and Geraldo Rivera. In another chapter, Bradbury discovers an astonishing family secret and her link to a nefarious character.

Through it all, he maintains a sense of integrity and humanity, even in detailing some law and order professionals who took the wrong path and made bad ethical and legal choices.

One particular moving tale is about the unlikely friendship he formed with a bright but cold-blooded killer Richard Durkee who he visited at High Desert Prison.

“Do you visit all the people you send us?” a guard asks Bradbury.

“No, this one is special. We go back a long way. He says I’m his only family.”

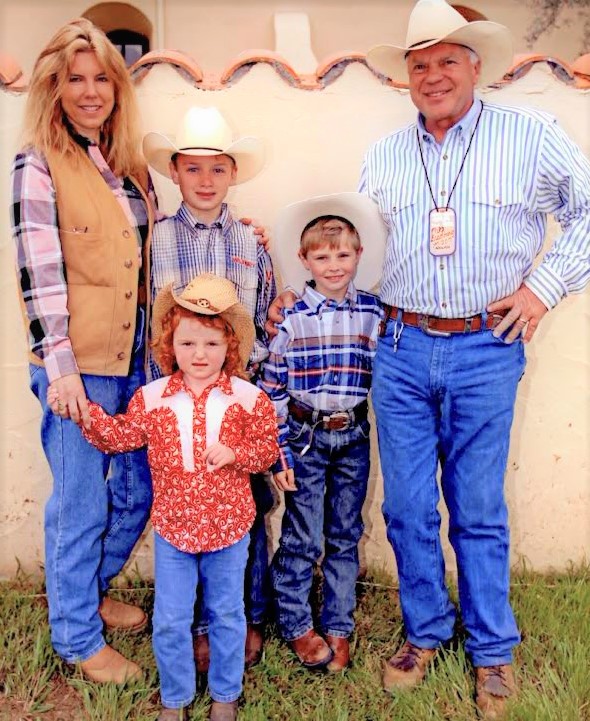

Besides former Gov. Wilson, Bradbury has rubbed shoulders with other powerful people and Law & Disorder has a gallery of photos of them, along with family memories. People like former U.S. presidents Ronald Reagan, George Bush and George W. Bush, Senator John McCain, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and actors Jimmy Stewart and Bob Hope.

Among Bradbury’s notable accomplishments was serving on Reagan’s Commission on Drunk Driving. It was a cause he took seriously as he did the law in general and how it has been applied in his country. For instance, he writes about the “kabuki dance” in the U.S. between periods of lax enforcement and light sentences to tough justice and he criticizes both approaches.

If Law & Disorder didn’t hook me in its earliest pages, Bradbury seals the deal in his concluding chapter when he remembers, among other things, boarding a flight to Seattle and encountering his namesake, the famous writer Ray Bradbury, on the plane. Bradbury the former DA’s respect and admiration for Bradbury the famous writer put the writer of this fine memoir in my good books.

Law & Disorder is available at Terry McConnell’s website.

Claudio D’Andrea has been writing and editing for newspapers, magazines and online publications for more than 30 years and has published a book of short fiction, Stories in the Key of Song. Visit him at claudiodandrea.ca or read his stuff on LinkedIn and Medium.com.

Leave a comment