A tribute to Alistair MacLeod

Originally published in Curiosity Never Killed the Writer on April 23, 2018.

We had an earthquake the other day.

It was no great shakes. Literally. It only registered 4.1 on the Richter scale. There were no reports of injuries or property damage — not even pictures falling from the walls. Still, it got a lot of buzz down here in Tornado Alley and whipped up more than one meme on social media. Some of them were pretty funny.

For me, the great Windsor Earthquake of 2018 brought back memories of another rumble back during my days in university. It also stirred in me a deep appreciation for a great teacher and an even greater artist: Alistair MacLeod.

***

It was Jan. 31, 1986. I was sitting in a classroom at the University of Windsor’s Dillon Hall, listening to a lecture on the English Romantics by the late, great Canadian writer. A 5-scale earthquake shook the room. I remembered feeling my desk slide slightly to the right and seeing the desk ahead of me move.

“Did we just have an earthquake?” MacLeod asked the class?

A few years later, I would meet up with him again at Douglas College in New Westminster, B.C. MacLeod was writer-in-residence and I was a reporter for a community newspaper. At the time, MacLeod was an esteemed short story writer whose output was few and far between because, as one writer noted, he took his time crafting one perfect sentence before moving on to the next.

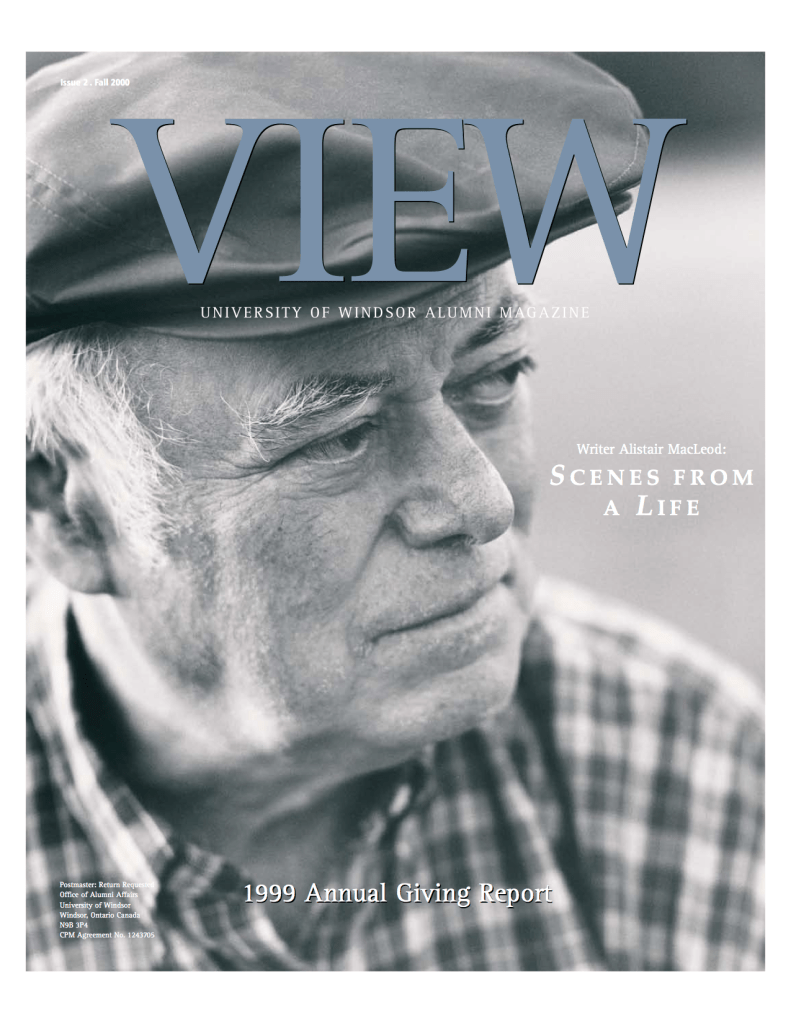

Almost a decade later, MacLeod wrote his one and only novel, No Great Mischief, a critical and popular blockbuster. I met up with the Cape Bretoner again, back at his home-away-from home in Windsor and my hometown where I returned from working out west. Writing for the University of Windsor’s View magazine under the pen name Paul Riggi, I was asked to do a profile of MacLeod — a dream assignment — and it appeared on the cover along with the stunning images of photographer Kevin Kavanaugh.

It took dogged persistence to arrange the interview with MacLeod, his schedule filled with appointments in the wake of the success of that novel, but here I was again, sitting down with the master in the shadow of a windmill in Olde Sandwich Town just west of the university.

By then, it had been years since I was in his classroom, a good but not great English student taking my one and only undergraduate course taught by MacLeod. I reminded him about the earthquake.

At first, it seemed as though the event — and I— were lost in the proverbial mists of time.

But then MacLeod looked past my shoulder as if conjuring a spectral guide and spoke:

“I was facing this way,” he said, as though painting the memory with one outstretched arm then lifting up the other, “and you were facing that way.”

My jaw dropped. He remembered the scene perfectly.

They say great teachers have an uncanny ability to remember tiny details about students. Great artists, of course, have acute powers of observation.

Here was Alistair MacLeod in both roles before my very eyes.

The man who wrote the classic last line in No Great Mischief — “All of us are better when we’re loved” — could not comprehend the impact that his remembering that detail would have on this student could he?

***

A year later, I met up with Alistair MacLeod again. He was giving a reading at the university following the release of his collection of short fiction, Island. I asked the master if he would sign my book.

MacLeod held the book open for a minute to think, then put pen to paper. When I opened it, my jaw dropped again at what Alistair MacLeod — the man revered and loved across Canada and beyond, who one critic called “the greatest living Canadian writer and one of the most distinguished writers in the world” — wrote:

Leave a reply to Claudio D’Andrea Cancel reply